Frequently asked questions

things people ask us all the time

About the definition of communities of practice

Communities of practice are sustained learning partnerships among people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.

For a more extensive definition, see our our page on communities of practice.

A team is held together by a task. When the task is accomplished the team disperses. Team members are likely to learn something in the performance of that task, but this learning does not define the team. It is the task that keeps them together. And it is their respective commitment and contributions to the task that is the main source of trust and cohesion among them.

A community of practice is held together by the “learning value” members find in their interactions. They may perform tasks together, but these tasks do not define the community. It is the ongoing learning that sustains their mutual commitment. The trust members develop is based on their ability to learn together: to care about the domain, to respect each other as practitioners, to expose their questions and challenges, and to provide responses that reflect practical experience.

In an organization, a team delivers a product or a service. A community of practice delivers a capability.

The domain of a community of practice is usually a strategic capability essential to the mission of the organization. This creates a focus that it different from teams. While communities or practice do help their members achieve their goals in their respective teams, projects, or business units, their focus on delivering a strategic capability also tends to give them a broader and more long-term view oriented to the sustainable success of the organization.

A task force is a special type of team pulled together to address a specific problem, usually of broad scope. Often people are selected in order to represent an organization or a perspective in the negotiation of a solution. It is their commitment to the process that keeps them going and respect for the voices they represent that builds trust.

A community of practice is a learning partnership. Members may come from different organizations, unites, or perspectives, but it is their engagement as individual learners that is the most salient aspect of their participation. Their learning my aim to benefit their organizational unit, but they are not there as representatives to deal with the politics of coming to a decision.

All communities of practice are networks in the sense that they involve connections among members. But not all networks are communities of practice: a community of practice entails shared domain that becomes a source of identification. This identity creates a sense of commitment to the community as a whole, not just connections to a few linking nodes.

Communities and networks are often thought of as two different types of social structure. From this perspective, one would need to ask the question: given a group, is it a community or is it a network?

We prefer to think of community and network as two aspects of social structuring, which require different forms of developmental work.

- The network aspect refers to the set of relationships, personal interactions, and connections among participants, viewed as a set of nodes and links, with its affordances for information flows and helpful linkages.

- The community aspect refers to the development of a shared identity around a topic that represents a collective intention—however tacit and distributed—to steward a domain of knowledge and to sustain learning about it.

There are groups where one aspect so clearly dominates that they can be considered “pure” communities or “pure” networks. A personal network, for instance, is rarely a community as people in the network are not likely to have much in common except for being connected to the same person in various ways; and they may not even know about each other (even though they are potentially connected from a networked perspective). Conversely the community of donors to a cause may feel a strong allegiance and identity with the cause they share. They know about each other because they know that there is money flowing toward the cause beyond their own donations. And yet they do not necessarily form a network (except potentially), as there may not be any interactions or direct connections among them.

For most groups, however, the two aspects are combined in various ways. A community usually involves a network of relationships. And many networks exist because participants are all committed to some kind of joint enterprise.

From this perspective, the questions one would ask are: given a group, how are the two aspects intertwined and integrated, how do they contribute to the cohesion and functioning of the group, and which one tends to dominate for which participants? And at any given time, which aspect needs to be developed as a way to increase the learning capability of the group?

About cultivating communities of practice

You cannot start a community by yourself. In fact you cannot start a community at all, to be quite honest about it. The only people who can form a community are the members themselves as a collectivity. But this does not mean that you cannot do anything if you see the need for a community that does not exist yet.

- The first step is to have a series of conversations with potential members. What issues and challenges are they facing? Do they interact with others facing similar issues and challenges? Do they think it would help to make such interactions more sustained and systematic?

- The second step, which often happens in the context of the first one, is to find some potential members who are willing to join you in your vision of a community of practice and to invest their own identities as practitioners in making this happen.

- The third step, assuming the first two have yielded positive results, is to engage a dedicated core group from the second step in designing a process by which the community can get going. Often this will entail organizing a launch event. But in some cases, it could just entail starting working on an issue and letting the process attract others. The level of visibility of the launch process will depend on the degree to which it can build on existing identities associated with the domain of the community.

Community formation takes time, but the time it takes for a community to become fully operational varies a lot from case to case. Some communities are so ready to exist that they congeal as soon as members have an opportunity to start learning together. Members can see the value of connecting with each other even before they start. Other communities begin much more tentatively. Members have to experience the value of learning together over and over before they are ready to make a commitment. But in general, one could expect a community to really get going and produce value within months and become mature in less than a year.

There really is no set length of time that a community should last. In most cases, a community of practice starts without a clear sense of how long it will exist. It will last as long as members find value in their learning together. The intensity and relevance of this value are more important than the duration of the group. Some communities exist for a very short time and some last for years. Of course just one encounter will not make for a community: some level of sustained interaction is required over time. But a community should be allowed to disperse as soon as it has lived its usefulness.

Being a community of practice does not depend on size. It depends on identification with the domain and enough mutual engagement to produce learning value.

Of course, if a community is very small, members will likely have heard each other’s stories and opinions after a while. Without new blood or more people, interactions often become stale, unless the domain is extremely dynamic and presents new, exciting challenges all the time.

If a community becomes very large, intense interactions will be more difficult. The community will tend to spawn smaller subgroups based on specialized interest or geographical proximity. But if one considers different levels of participation, as long as an active core group sustains enough engagement, there is no limit to the number of people who might benefit from the learning that takes place (especially with new technologies that enable peripheral participation across time and space).

Participation in communities of practice is rarely a person’s main activity or job, so expected levels of participation should reflect this reality. Mainly they should reflect the level of relevance of the domain to the main activities of members. This means that levels of participation will likely be quite different for different people. It is not unusual to have a smaller core group of members who identify very strongly with the community and contribute most of the activity—with concentric bands of participation from very active members to merely passive observers (or so-called lurkers on the web). This disparity is usually not a problem as long as it reflects personal interest in the domain and not some other distinction, such as headquarter versus field or language fluency. In a healthy community there is usually a flow of people moving across these levels of participation.

Communities of practice are complex social structures, whose voluntary and self-governing nature makes them quite sensitive to subtle dynamics. As a result a host of factors potentially contribute to their success (and to their failure). Any of them can become critical in some circumstances, but if we are asked to name our top three, we generally mention the following:

- Identification: Communities of practice thrive on social energy, which both derives from and creates identification. Passion for the domain is key. This makes the negotiation of the domain a critical success factor.

- Leadership: A key success factor is the dedication and skill of people who take the initiative to nurture the community. Many communities fail, not because members have lost interest, but simply because nobody has the energy and time to take care of logistics and hold the space for the inquiry.

- Time: Time is a challenge for most communities, whose members have to handle competing priorities. Theoretically, time should not be an issue if the interest is there, but practically it remains a constant challenge. Because time is at such a premium, a key principle of community cultivation is to ensure “high value for time” for all those who invest themselves.

Other candidates for success factors include: self-governance, a sense of ownership, the level of trust, recognition for contributions, high expectations for value creation, organizational voice, connection to a broader field, interactions with other communities.

The issue of measurement and assessment is a controversial one when it comes to communities. Some see measurements as community killers and some see them as the only way communities can survive in organizations. The reality of most communities is more nuanced. While it is true that red tape can harm a community, some awareness of the value created can also inspire members and legitimize their participation and personal investment. And while demonstrating value to an organization is important to ensure support and sponsorship, trying to measure everything is not always the best way to make the value of a community understandable. This calls for a very pragmatic attitude.

Communities of practice can produce some very tangible outcomes, such as time savings or documents, whose value can be measured. At the same time a good part of the value of having a community is less tangible and difficult to assess, such as the level of mutual trust, commitment, and inspiration. Often the existence of a community can be readily justified by accounting for the tangible outcomes and assuming that less tangible aspects come as a bonus.

Practically, since time is often the most difficult challenge for communities, one needs to consider carefully how much of their precious time available for community participation members should devote to justifying the existence of their community. Much of this depends on the context and on the level of direct investment in communities.

One principle to remember when thinking about measurements applied to communities and learning in organizations is that the true management of knowledge processes requires intelligent conversations. If measurements are in support of intelligent conversations about real value creation, they tend to be useful. But if they are a substitute for such conversations, they tend to become counterproductive.

About communities of practice in organizations

Communities of practice are the perfect vehicle for involving practitioners directly in the development of the key capabilities that their practice is a part of. As a result they engage in the development of strategic capabilities critical for achieving the goals of the organization(s) they belong to. For instance, consulting firms cultivate communities of practice so that when clients interact with a consultant they actually have access to the knowledge and intelligence of the whole firm, not just one person. Schools cultivate communities of practice so that teachers move from being lonely practitioners to offering their students the pedagogical creativity of the whole community. Governments encourage communities of practice to learn and find synergies across agencies. Non-governmental organizations are finding that communities of practice provide new ways to foster international development by connecting practitioners from various countries to exchange and explore ideas among peers.

Communities of practice have always existed in organizations, but they have lived “underground” so to speak. The formal and informal parts of organizations have lived parallel but separate lives. In a knowledge economy, this benign neglect is no longer possible. Creating and leveraging knowledge is not amenable to industrial command-and-control hierarchies. It is now essential to legitimize, engage, and integrate into the organization the communities that sustain the capabilities necessary to its success.

Communities of practice will not break silos, but they do create bridges across them.

Large organizations tend to swing between centralization and decentralization. Communities of practice offer another way to deal with the trade-offs involved. Because they are learning partnerships and not regulating entities, they can create synergies across silos without imposing the type of top-down homogeneity that centralization tends to demand. But because they foster discussions of practice across organizational units, they are a counterweight to the type of fragmentation that can result from decentralization.

Traditionally, knowledge has been viewed as something that experts hand down to practitioners. But organizations in all sectors are discovering that something unique happens when practitioners become direct learning partners by forming a community: they bring insights from their engagement with customers and practical challenges; the knowledge they share and create together builds on these insights and challenges; and they can apply this knowledge to their work because it reflects their experience.

Admittedly, the experience of practitioners cannot be the source of everything they need to know. So there is definitely a role for specialized experts and researchers. But the contributions of these experts and researchers are more meaningful and useful when they are integrated into an ongoing learning process that is driven by practitioners themselves.

In order to reflect the experience of practitioners, a community of practice needs to be self-governing in a fundamental sense. This way, practice can really become the curriculum—in the sense of providing both learning challenges and learning resources likely to be relevant.

If organizations are going to cultivate communities, in their midst or across their boundaries, they have a responsibility to create a context in which these communities can thrive. Large numbers of communities of practice today live inside or across organizations that influence them in many ways. And most of the failures of these communities are at least in part due to a lack of organizational support or understanding. So the organizational side of the cultivating equation is a critical success factor.

Organizations are only beginning to learn how to integrate communities of practice. The point is not to institutionalize them and shape them into the image of the formal organization, but to create “hooks” into formal systems for recognizing, engaging, and supporting them. One big lesson is that bureaucratic processes do not work well for this purpose. Leading organizations are learning that intelligence cannot be designed out of the process. Therefore the key principle is to use formal structures to create spaces, processes, and opportunities for intelligent conversations. Examples include:

- Leveraging hierarchical positions to discuss the strategic importance of learning and the role of communities of practice in enabling it

- Formalizing roles and relationships like community leadership and executive sponsorship to create opportunities to explore the strategic value of communities, their contributions, their perspectives, and their need for resources

- Tuning formal processes like performance appraisal so that individual contributions can be discussed and recognized meaningfully

- Establishing a dedicated support function to address the logistical, educational, and infrastructural needs of communities and help orchestrate the whole learning system and required strategic conversations.

Successfully enabling this hybrid combination of vertical and horizontal structures is going to be one of the main challenges of the organization of the twenty-first century.

There really is no set length of time that a community should last. In most cases, a community of practice starts without a clear sense of how long it will exist. It will last as long as members find value in their learning together. The intensity and relevance of this value are more important than the duration of the group. Some communities exist for a very short time and some last for years. Of course just one encounter will not make for a community: some level of sustained interaction is required over time. But a community should be allowed to disperse as soon as it has lived its usefulness.

Because of this tension between vertical and horizontal processes, integrating communities of practice in an organization is an exercise in paradox. Organizations tend to pay attention to structures or issues by institutionalizing them but it is a delicate task to integrate communities of practice into the organization without squelching the very self-organizing principle that makes them thrive. When it comes to communities of practice, organizations have varying degrees of institutionalization, which even vary from community to community. It is useful to distinguish between two kinds of institutionalization: institutionalizing communities of practice themselves, and institutionalizing their existence in the organization.

Institutionalizing communities. There are cases in which institutionalizing a community makes sense. When the domain is of critical strategic importance, it may require the investment of substantial resources, including some full-time core members. Some communities include a center of excellence; some even become departments in the organization. But even when they do, it is useful to maintain a distinction between the formal center or department and the community of practice it represents. For one thing, their boundaries are likely to be distinct—some members of the community may not be part of the department, especially the more peripheral ones. And the underlying community may well have different sources of motivation, qualities of relationships, and governance expectations. The institutional part is often best understood as the core of a broader community.

Institutionalizing the existence of communities. Institutionalizing a community into a formal structure requires caution; but it is always helpful to consider ways to institutionalize the existence of communities of practice in an organization—the fact that they are integral to the organization’s ability to achieve its goals. (This is true whether the relevant communities are fully inside an organization or exist across organizations.) Institutionalizing their existence can give them access to executive sponsorship and to resources, such as time, travel, and technology. Time is a good example because it is invariably a central concern for community members in organizations. Institutionalizing the existence of communities helps legitimize the time members spend on their communities without dictating what they do. Participation in communities can also be integrated in HR processes, such as developmental plans, training, and career advancement. This type of institutionalization aims to structure an explicit organizational context for communities. It does not reach into communities, nor attempt to substitute for the practitioners’ self-governance. It is a way to integrate communities by carving a special place for them in the organization, not by molding them in the image of the organization.

Being a community of practice does not depend on size. It depends on identification with the domain and enough mutual engagement to produce learning value.

Of course, if a community is very small, members will likely have heard each other’s stories and opinions after a while. Without new blood or more people, interactions often become stale, unless the domain is extremely dynamic and presents new, exciting challenges all the time.

If a community becomes very large, intense interactions will be more difficult. The community will tend to spawn smaller subgroups based on specialized interest or geographical proximity. But if one considers different levels of participation, as long as an active core group sustains enough engagement, there is no limit to the number of people who might benefit from the learning that takes place (especially with new technologies that enable peripheral participation across time and space).

In general, it is much better to let participation be voluntary. This way, communities of practice live on because they create value for members, not because of an edict or a box to check. It does not mean that one cannot strongly encourage participation or even request that someone run an idea by the relevant community. But making participation compulsory more generally runs the risk that communities become just another meeting to go to and survive. This is likely to deflate the very social energy that makes healthy communities of practice places of meaningful learning.

Communities of practice that have high expectations about what they can achieve tend to be energized. And yet misplaced tasks and expectations can also make the community feel like just another job to do. So the question tasks and expectations hinges on a key distinction between energizing and de-energizing tasks and expectations:

Energizing tasks and expectations. They usually allow practitioners to make a difference with their expertise; they help them connect with each other around their desire to perfect their craft; they have visibility in the organization (or at least with the people who can appreciate the results). Typical examples include solving hard problems, debating a hot issue, or inspecting a competitor’s products.

De-energizing tasks and expectations. They feel like an imposition and make community participation seem like work as usual; they do not entail much learning; and they do not reflect the real value of the community. Typical examples include collecting data, logistics, writing, or answering the same basic questions over and over.

Obviously, this distinction is a subjective matter and the same task or expectation can have either effect depending on the circumstances. Still, we have found the distinction useful because it seems to matter much more than where the task or expectation originated. The critical issue is not whether a given challenge was initially self-generated or suggested from the outside. A technical question from the CEO can be energizing; and a member’s suggestion to review the literature de-energizing. The critical issue is energy. The source of energy in community participation can be an instrumental benefit such as saving time, but just as often, it is learning, excitement, and professionalism. A hallmark of a mature professional identity is a desire to make a difference.

Communities of practice can be propelled forward by energizing tasks and expectations; they can be killed by de-energizing ones. We have seen it happen. Communities of practice can be viewed as a convenient resource to perform tasks for which there is no funding. No matter how much you care about a domain of knowledge, if participation in your community inevitably results in hours of undesirable homework, you’ll want to stay away. If an organization is going to ask communities of practice to perform tasks that are not energizing, but for which they are uniquely qualified, then it needs to fund these tasks explicitly and offer logistical support.

Wouldn’t communities become a threat to the organizational hierarchy?

Existing across an organization’s formal structures, communities of practice rarely derive much power directly from positions in formal hierarchies. But communities do not usually seek positional power, with its control over resources and accountability for investments—tasks for which communities are not well suited. They do seek the power of voice, however: the power to be heard, to make a difference, and to have their practice-based perspective matter. In the knowledge economy, the power of voice becomes just as important as the power of position.

In an organization where the power of voice is acknowledged, managers would routinely ask: “Have you checked with your community about this? What was their reaction?” The one time we saw a community really angry was an occasion when its opinion had not been sought. The company had gone ahead with an acquisition in the domain of the community and the acquisition had not turned out well. Members of the community’s core group were furious that their community had not been consulted. The community, they were certain, could have foreseen the problems. Interestingly, they were not asking for the responsibility to make the final decision. They did not care for the politics associated with such responsibility. But they wanted their voice to be included in the debate.

Executives who sponsor communities bridge between these two forms of power. A sponsor uses positional power to help communities find a voice in the organization. This integrating function is a new and sometimes uneasy role for executives to assume, because it does not identify power with control. Still it is a critical role, whose importance will increase with the growing emphasis on knowledge—and with it on the power of voice.

Knowledge is indeed a source of power; but hoarding knowledge is not necessarily the best way to benefit from its power, especially in the context of communities of practice.

Generalized reciprocity. In a community of practice, sharing knowledge is neither one-way nor merely a transaction. It is a mutual engagement in learning among peers. An improved practice benefits the whole community. Even experts benefit from having more knowledgeable colleagues. Contributing one’s knowledge is an investment in the stock of the community. In this context, the distinction between self-interest and generosity is not so clear.

Reputation platform. A community of practice acts as a platform for building a reputation. It is a long-term interaction through which people get to know each other. Peers are in a position to appreciate the significance of each other’s contributions in ways that make their recognition meaningful. And because communities of practice usually cut across formal structures, reputation can extend beyond one’s unit. As one engineer put it: “The advantage of my community is that it allows me to build a reputation beyond my team.”

With reciprocity and reputation combined, sharing becomes a major vehicle for realizing the power of knowledge. But it is often important that this process extend beyond the community and become an aspect of the integration of communities in organizations. This calls for mechanisms to translate community contributions and reputation among peers into organizational recognition, such as a rubric in performance appraisal for community contributions and career paths for people who take on community leadership.

Organizational culture can work against communities of practice, if it is individualistic, competitive, and focused on the short term.

Changing organizational culture is very difficult. Change initiatives to address cultural issues have had mixed results at best. One of the problems of these change initiatives lies in their scale: they have to happen in lockstep across the organization. As a result they remain for the most part distant from people’s daily concerns.

Communities of practice are very sensitive to culture because of their voluntary nature and their basis in identity. But for the same reason they are also a locus for the creation of culture. Each community inherits the culture of the organization, and needs to build on what the culture offers. But being self-governed, it can to some extent choose to produce its own culture. This process does not even need to be deliberate.

Cultivating and integrating communities of practice is therefore likely to lead to a kind culture change in the long term, but one that takes place a community at a time. It is therefore less controlled and less uniform than traditional initiatives. But being in the hands of practitioners increases its chances of “taking.”

Participation in communities of practice is rarely a person’s main activity or job, so expected levels of participation should reflect this reality. Mainly they should reflect the level of relevance of the domain to the main activities of members. This means that levels of participation will likely be quite different for different people. It is not unusual to have a smaller core group of members who identify very strongly with the community and contribute most of the activity—with concentric bands of participation from very active members to merely passive observers (or so-called lurkers on the web). This disparity is usually not a problem as long as it reflects personal interest in the domain and not some other distinction, such as headquarter versus field or language fluency. In a healthy community there is usually a flow of people moving across these levels of participation.

About social learning spaces

A social learning space is a particular way of engaging in learning with other people. It arises out of three characteristics:

- Caring to make a difference. Participation in the space is not perfunctory or compliant but people are there because they want to learn how to make a difference they care to make (whether or not they can articulate this difference).

- Engaging uncertainty. Participants engage in the space on the edge of their knowing how to make a difference. Their engagement is led by what they don’t know rather than what they do know.

- Paying attention. Participants pay attention to responses -effects, reactions, feedback, data – as it might help them make the difference they care to make

We view social learning spaces are a foundational unit in social learning theory.

- The focus is on people and their participation

- Members drive the learning agenda

- Learning is rooted in mutual engagement that pushes the participants’ edge of learning

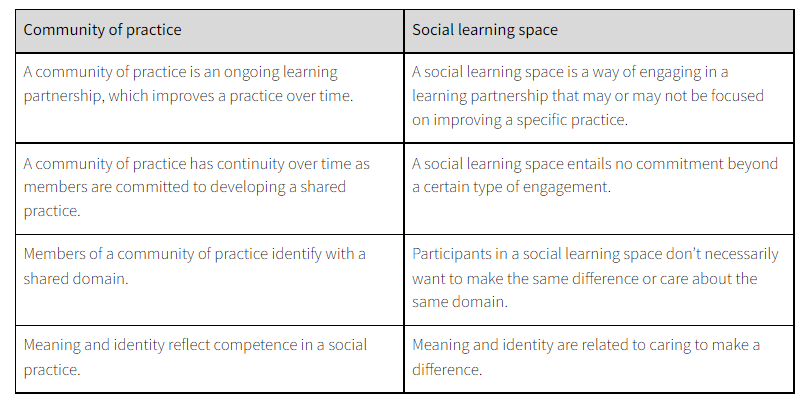

Over time a social learning space might become a community of practice, but not necessarily. And if a community of practice becomes rather ossified, it can be a good idea to shake it up with some social learning spaces.

A social learning space may take place spontaneously (for instance, round the dinner table) or be an intentional space designed as a series of meetings with an agenda and facilitation.

Our work on systems convening is an evolution of our work on social learning theory and practice. It did not spring from systems theory. Most of the people we worked with or interviewed were not trained in systems theory or systems thinking. They simply saw that they needed to bring a broad range of people and perspectives together to achieve something they thought needed doing. This led them to deal with boundary interactions across practices and organizations and to address issues of personal and institutional power. In this sense, systems convening is a pragmatic endeavor and not a derivative of systems theory, even if there are parallels in their insistence on embracing complexity.

About social landscapes

A social landscape refers to the broader context in which learning takes place. The kinds of things that constitute the social landscape in which you operate include:

- Systems: designed, and relatively fixed, things like institutions, projects, and artifacts

- Practices: things that people actually do and ways of doing things that they have been developing

- Relationships: the ties that connect people

Taking a social landscape perspective is to recognize that what you do and learn is shaped by systems, practices, and relationships—and that your learning and actions also shape this landscape.

Like a natural landscape, a social landscape has all sorts of features that make it into a rich place to live in. A social landscape highlights the importance of history in shaping systems, practices, and relationships. And how the systems, practices, and relationships being built today will shape what history will look like tomorrow. It is social in the sense that it is constantly under construction and subject to the decisions, resistance, and political circumstances that came before.

To the extent that online is a place where stuff happens, it is just as much a part of a social landscape as other spaces. Cyberspace has become an integral part of the context in which we live our lives, This includes the systems and policies that shape the online world, the practices people are creating to make things happen there, and the relationships online enables. Cyberspace is then an integral part of the landscape, regardless of how much time you spend there.

About systems convening

Systems convening refers to the work of people who develop new learning partnerships and new learning capability across boundaries in a social landscape.

You can read more about it on our page on systems convening.

Our work on systems convening is an evolution of our work on social learning theory and practice. It did not spring from systems theory. Most of the people we worked with or interviewed were not trained in systems theory or systems thinking. They simply saw that they needed to bring a broad range of people and perspectives together to achieve something they thought needed doing. This led them to deal with boundary interactions across practices and organizations and to address issues of personal and institutional power. In this sense, systems convening is a pragmatic endeavor and not a derivative of systems theory, even if there are parallels in their insistence on embracing complexity.

About value creation

If you focus on learning for people actively engaged in a drive to make a difference that matters to them, then thinking of value creation makes a lot of sense. When the drive to make a difference focuses peoples’ attention on what’s working or not, they have a chance to improve and refine their ability to make that difference. In other words, people who care to make a difference are continuously evaluating whether or not what they are learning is going to help them. This is why we propose to look at social learning in terms of value creation.

Yes, it is. But we are suggesting that a concern about value creation is much broader—it is an integral part of social learning for all. And ideally, when evaluators are involved, they should be able to quickly provide participants with data and feedback relevant to their aspirations. In practice, some things can get in the way:

- Evaluators often don’t know what members’ aspirations are, especially when indicators and data sources are set by funders, managers, or people outside the social learning space.

- When aspirations are viewed as goals or objectives, formal evaluation tends to focus on whether these goals are achieved, ignoring hopes, aspirations, possibilities, and circumstances that emerge along the way.

- Formal indicators often focus on easily measured surface features, such as numbers of participants, meetings, or downloads, which do not capture the value of the learning to participants in pursuit of their aspirations.

- Evaluators have to show observable changes within a certain timeframe. This is not necessarily aligned with the series of micro-changes that matter to the people who care to make a difference.

Undertaking an evaluation from a value-creation perspective starts with participants’ framing of their aspirations. It then follows their learning as it addresses, and possibly reframes, these aspirations.

Value creation is a framework rather than a method. It does not dictate how it is used. But it does have general methodological implications: seeking descriptions by participants of the value they get from a learning partnership and how this has influenced their ability to make the difference they want to make. We call these descriptions value-creation stories. These stories can be cross-referenced with indicators (often quantitative) of the effect of learning. And they can also suggest indicators to monitor in data collection.

About social learning ethic

- What am I doing to get better at articulating the difference I want to make?

- How good am I at speaking frankly to myself – about difficult questions, about things I don’t know, about what’s working or not?

- Am I leveraging who I am to open new spaces for learning or to cross boundaries in the situations in which I find myself?

- What do I do to create new learning alliances or refresh old ones?

- Who are my learning partners? What different voices do they bring to the table? Are there voices in there who are challenging my blind spots?

- To what extent is a social learning ethic embedded in my approach to life and my relationships with others?